Tags:

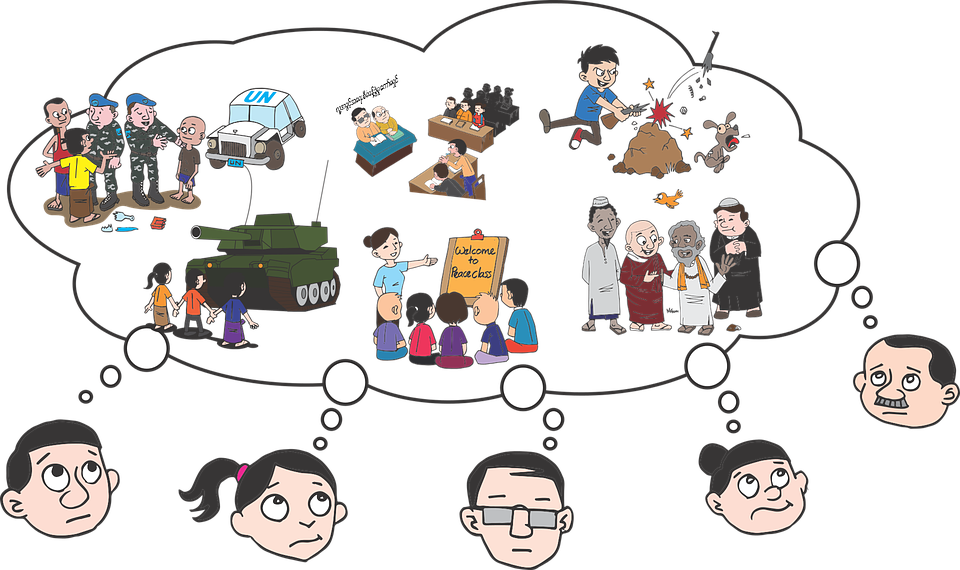

The Albanian-Serb conflict has no religious dimension. It is purely secular. But political leaders have often manipulated and co-opted religious thought and religious institutions to advance their political ends, undermining the religion’s credibility as an autonomous and benign entity. Religion has not promoted the conflict in Kosovo directly, but it has not acted as a source of peace, either. Serb and Albanian religious peace-promoting and reconciliation voices are rare. Despite these shortcomings, the religious institutions could play a significant role in promoting ethnic reconciliation between Serbs and Albanians in Kosovo, a process that would simultaneously complement the local and international secular efforts to bring permanent peace between Kosovo and Serbia. Religion and Albanians have had a weak relationship. Unlike the Serbs, the Albanians are divided intro three religions: Muslim, Catholic, and Orthodox. The Muslims, who constitute the overwhelming majority, are also divided into two groups: Sunni and Dervish. Given these divisions, the religion could not play a unifying role in the Albanian society, so it was not a relevant factor in the Albanian national development. Even Islam, as the dominant faith, failed to penetrate the Albanian society beyond ritual observation. Albanian nationalist movements also discouraged devotion to Islam, considering it an imposed foreign influence. National ideologists propagated a kind of ‘civic religion,’ epitomized in Pashko Vasa’s famous nationalist verse, 'the faith of the Albanians is Albanianism.' Neither Islamic leaders, nor Islamic theology did play a role in Kosovo’s political mobilization. Muslim leaders did not support or take part in various Albanian nationalist movements in Yugoslavia and played no role in the 1990s national mobilization. A moderate, non-political version of Islam, mixed with cultural traditions, predominates in the Albanian society. Post-war efforts of various Islamic fundamentalist organizations to spread a more extreme version of Islam were short-lived. Religion and Serbs have a much stronger relationship. Orthodoxy is an important component of the Serb national identity. The Serb Orthodox Church, unlike the Mosque, existed as an institution and played an historical role in defining the Serb identity. It is also considered an authentic Serb institution. The Church has considerable political influence, particularly on the Kosovo issue. The seat of the Serbian patriarchate is located in Kosovo, and, so, religious passions remain a major factor in Serbia’s rejection of Kosovo’s statehood. While Albanian nationalism regards Islam as a foreign influence, the Serb nationalism considers Orthodoxy as a valuable national element. Though neither Serbs, nor Albanians have high levels of religious beliefs and affiliations, religious organizations can still play a role in promoting reconciliation between the two formerly warring societies. Religion could serve as a source of values to confront prejudice and misunderstandings, promote tolerance, and set new social norms and standards for multiethnic coexistence. Religious leaders can use religious ideology and thinking as a means to legitimize reconciliation and forgiveness. Unlike politicians, religious leaders seem to be driven by public interest more than by personal profit, thus having more legitimacy to address sensitive issues. Through informal interactions with members of both ethnic communities—religious, political, and civil society—they can help restore the relatively respectful pre-war relations between the Serbs and Albanians. The war disrupted many social networks that had existed for many years. The social dialogue would, simultaneously, improve the religion’s public reputation. The Albanians continue to perceive the Serbian Orthodox Church as a source of hatred, and the Serbs do not see Islam with a friendly eye, either. A number of mosques and churches were targeted during and after the war. Invoking values of empathy, forgiveness and nonviolence, the religious leaders could help shape the debate on reconciliation. These values are just as important in post-conflict ethnic reconciliation, as in religious practice. The leaders could bring these values from religious to the social and political arena. A social dialogue based on these values could help modify public opinions and attitudes and eventually contribute to break the ethnic hatred cycle, in which the Albanian and Serb societies have been trapped for decades. The leaders’ approach could be not to redefine the past or reach common interpretations, but, rather, to figure out how to learn to live together with these differences, and, ultimately, turn away from dead-end paths of ethnic politics - something the secular efforts have failed to achieve. The secular peace efforts, centered in the Brussels dialogue, have not been successful in bringing about reconciliation, though they did resolve a number of important practical issues. The political dialogue amplified ethnic differences and revived old myths. The Albanian and Serb societies and their leaders seem just as unwilling now, as they were twenty years ago, to take bold steps towards genuine and sustainable reconciliation. Myths and prejudice continue to shape the Serb-Albanian relations. Albanian Islam and Serbian Orthodoxy have respected the separation of religion and state and are committed to democratic values. In addition to promoting reconciliation, they could also play a role in democratization: for example, through speaking up against corruption.

Soon after the conflict, the war leaders began to like wealth, and the only way they knew how to get to it was by capturing the state. These war leaders turned into politicians who win elections through intimidating campaigns, patronage and outright theft. Religious leaders do not have to be simple observers.